How to think about False Solutions in the Food System – an introduction.

They say the road to hell is paved with false solutions.

This week I am in New Orleans - glad to be speaking at the ‘Systems Change’ conference of Friends of the Earth International - the world’s largest grassroots environmental federation. I’ve been asked to give a quick overview of ‘False solutions in the food system’. Since my ‘podium time’ is limited, I thought it would be helpful to provide a much expanded version of that talk (including slides) here at ScanTheHorizon.org. If you find it useful, please do share it. I also want to acknowledge and flag this publication by the ‘Hoodwinked in the Hothouse’ collective whose work I am partly building on here 😊

They say the road to hell is paved with false solutions… or something like that.

Sometimes it’s hard to recognize these bad ideas at first. Therefore, I was asked to present a kind of “spotters guide” to false solutions in the food system.

Ideally, I would have liked to offer a full ‘taxonomy’ or a ‘here be dragons’ map of the terrain flagging exactly which ‘false solutions’ food activists (and others) should be watching to sidestep on our way to a better food future.

But there are just too many false fixes out there (and they are proliferating) so I concluded it may be more useful to step up a level and instead offer some general ways to think about this phenomenon of “false solutions”.

Perhaps using these insights folks can draw their own maps, charts, and taxonomies for spotting false solutions in the wild - or at least in the issues and regions in which they work.

Troubling solutionism

First a word on solutions.

Even after 30 years hanging around NGO ‘solutions campaigning’ (or maybe because of it) I still get uncomfortable when I hear the word ‘solution’ tossed into a campaign or activism strategy. That word evokes for me something between the bland optimism of a 1950’s corporate brochure (I think of General Electric’s: “Progress is our most important product”) and the marching jackboots towards “The final solution”. I recognise that in the 2020s, amidst the gathering anxiety of the polycrisis, ‘solution’ is a comforting word to many with its sense of certainty. But I feel that is illusory. Our polycrisis moment isn’t really going to resolve like that.

Today’s common conception of a “solution” is as an ‘explanation or answer’ that ‘solves’ or ‘resolves’ a stated problem. We are told that ‘fermented’ protein will “solve” the climate emissions problem of livestock, that GMOs will ‘solve’ hunger or that digital farming will “solve” the excesses of industrial agriculture.

Solutions like these promise a particular kind of dopamine hit. Think how a “solution” is that rewarding pay-off you get at the end of wrestling with a math problem. This kind of solution unwraps “the correct answer” to a stated puzzle. Getting there requires applying a certain type of technocratic cleverness to the problem at hand. It also requires the problem be first stated in very defined and countable, even engineerable, terms. In these days of Artificial Intelligence that sometimes means defining the problem as narrowly as a mathematical algorithm and then feeding it into a model full of data.

So climate change gets rendered as a puzzle of reducing carbon dioxide (or CO2 equivalents) in the atmosphere. Hunger gets rendered as a puzzle of managing access to adequate food calories. Biodiversity a puzzle of protecting ‘wild’ acres. This reductive approach substitutes for, plays down and often invizibilizes the very factors that create, complexify and entrench climate change, biodiversity loss and hunger in the first place: history, power relations, cultural forces, legal arrangements, economic oppression, patriarchy, racism and empire. Rendering climate change, biodiversity loss or hunger as simply “puzzles to be solved” leads us towards cheap, quick answers or ‘hacks’: fixes of various types.

Benjamin Bratton in his great TED talk provocatively called ‘What’s wrong with TED Talks’ names this as a matter of mistaken metaphors:

” Problems are not puzzles to be solved,” he says. “That metaphor assumes that all the necessary pieces are already on the table, they just need to be re-arranged and re-programmed. Its not true. Innovation defined as moving the pieces around and adding more processing power is not some Big Idea that will disrupt a broken status quo: that precisely is the broken status quo. If we really want transformation, we have to slog through the hard stuff (history, economics, philosophy, art, ambiguities, contradictions). Bracketing it off to the side to focus just on technology, or just on innovation, actually prevents transformation”.

I say ‘Amen’ to that.

It may be better to stop referring at all to climate change, biodiversity collapse or hunger as ‘problems’ (as in math problems) a but instead name them as something more like ‘situations’ or ‘troubles’ - with all of the layers of complexity and ambiguities those words invoke. Donna Haraway talks of ‘Staying with the Trouble’ in how we approach our interconnected crises. Like Bratton in the quote above, her phrase helps remind us that trying to “fix “our crises as though we are mending a broken engine is to fundamentally misunderstand the kind of trouble we are in.

It’s to fail to go a radical analysis (literally “to the root” ) of the troubles at hand. Sure, you can mend the engine of a car (or even make it electric) and feel good about that but cars wil still tear apart our communities and road injuries will still remain the 8th leading cause of death globally. What sort of fix is that?

Evgeny Morozov defines something called “Solutionism” in his excellent book “To Save Everything Click Here”. Solutionism, he says “refers to an unhealthy preoccupation with sexy, monumental and narrow-minded solutions - the kind of stuff that wows audiences at TED conferences - to problems that are extremely complex, fluid and contentious. They are the kinds of problems that, on careful examination, do not have to be defined in the singular and all-encompassing ways that ‘solutionists’ have defined them… Solutionism presumes rather than investigates the problem it is trying to solve, reaching for the answer before the questions have been fully asked”

So solutions and solutionism move too quickly to render a situation as a ‘solvable’ problem - usually in too narrow technical terms and without addressing root causes.

That is not going to dig us out of our current polycrisis hole.

Solutions as “solvent”

Interestingly the original Latin origin for the word “solution” provides a more useful concept. it goes back to the notion of a chemical ‘solution’ or “solvent”.

This sort of ‘solution’ means ”a loosening or unfastening," - like loosening a knot or loosening the chemical bonds.

Loosening bonds turns matter in a fixed state into a more fluid state - making change possible. When Silicon Valley talks about ‘disruptive solutions’ (so-called “moving fast and breaking things”) it is often talking about applying technologies as a solvent to loosen up commercial opportunities. We can also loosen up situations, introduce flexibility to make change possible.

But, as the toxicity warnings on chemical solvents attest, a solvent can be strong stuff and must be used with caution. What else do you loosen and break up when you apply ‘disruptive solutions’ as a solvent (communities, rights, ecosystems)?? And what about deliberate solvent abuse? (I’ll come to that…)

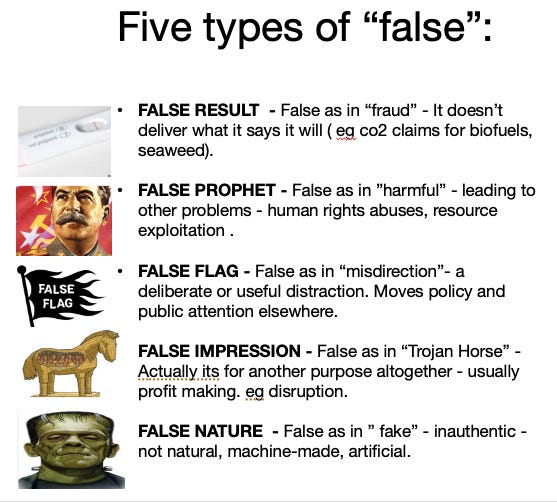

Five Forms of False

Having destabilized (loosened?) the word ‘solution’ let me also prod a bit at that other word: ‘False’.

I’ve come to appreciate that ‘false ’can mean different things to different people. I think it’s helpful to parse out these various meanings of ‘false’ when we talk of ‘false solutions’.

1. FALSE RESULT - This is False as in “fraud”. It’s the most straightforward type of false to contest without questioning solutionism per se. This is the sort of ‘false’ that points out that a thing simply doesn’t deliver what it says on the tin – that it fails on its own criteria.

This sort of false solution is abundant in the many types of proposals that make carbon dioxide-reducing claims. These may fail to count properly or may not account for the full context or life-cycle of an activity. This kind of false often gets activists into highly technical fights about dweeby details (such as carbon maths or hunger calories).

An example is the case of biofuels which it was claimed were ‘carbon neutral’ energy sources since the act of growing plants supposedly re-sequestered the very atmospheric CO2 that came from burning the fuels. It took quite an effort for civil society to point out that the land use change and soil disturbance associated with growing new biofuel crops was leading to a massive additional pulse of atmospheric CO2 emissions - not to mention all the uncounted CO2 from the energy it takes to grow, collect, process and transport biomass. The same thing is happening now with Seaweed.

2. FALSE PROPHET - This is when a solution is false as in ”harmful in other ways”. It’s what many environmental justice movements who fight against false solutions have uppermost in mind.

A proposed solution may promises to make one metric better actually makes a whole lot of other metrics worse - such as worsening human rights situations, increasing resource extraction and escalating community conflicts.

For an icon of ‘false prophet’ solutions, I‘ve used a picture of Joseph Stalin here on my slide But since we are talking about food I might have better used an image of Norman Borlaug whose “Green Revolution’ is the grand-daddy of modern false solutionism in the food system. Borlaug’s particular prescription of breeding high-input dwarf varieties of monoculture crops involved a mass unleashing of poisons and artificial fertilizers, a switch to commodity-driven monocultures and degradation of community agriculture models throughout Latin America, South East Asia and the Pacific.

Fights against ‘false prophet’ type solutions often involve showing the unacceptable “side effects” and also how the visions and understandings driving these activities are fundamentally incompatible with ecology and justice. Often it takes fighting for recognition that other metrics (social, cultural, spiritual) also matter.

3. FALSE FLAG - This refers to false as in “misdirection” - i.e. when a so-called ‘solution’ is touted in order to usefully distract from better alternatives. If a particular “solution” seems at first to be either bizarre or overly spectacular it may be that those proposing it have no strong interest in actually bringing it into widespread use but are rather using the spectacle of the idea as a token to distract and move policy and public attention elsewhere.

A great example of false flag solutionism (from the transport sector) is Elon Musk’s ’Hyperloop’ - a proposal to bore a pressurized tunnel from San Francisco to Los Angeles through which individual pods containing private cars could be accelerated at high speed - like firing a nail gun. Musk even has a private company called ‘The Boring Company’ supposedly working on hyperloop development. However, from the beginning, it has been apparent that the Hyperloop proposal was floated by Musk in order to distract and take political energy and investment away from a particular proposed high-speed public rail project in California. Musk, who controls the Tesla car company, is openly opposed to investment in public transport and wants to ensure future transport developments center private car ownership.

In the food domain, development’s such as The Impossible Burger, lab-grown meat and other alt-protein proposals have more than a whiff of ‘distraction’ and false flag solutionism about them. Hence the rabid enthusiasm for alt-protein by food processers, fast food companies and even meat companies, some of whom have now reinvented themselves as ’protein companies’. By ginning up a discussion on switching animal-derived proteins for GMO and monoculture ingredients they centre ultraprocessed industrial fast food culture as a vision of a sustainable future, distracting attention away from movements for agroecology, whole foods, local production and traditional diets.

Fights against this sort of false solution often emphasize the way a so-called solution comes wrapped in unproven hype and exaggerated claims.

4. FALSE IMPRESSION - This refers to false as in a “Trojan Horse”. That is when the so-called solution is not really designed for the purpose it appears to be but is actually fulfilling another primary purpose altogether - usually profit-making or ‘disruption’.

Digitalisation is a common area for these sorts of ‘trojan horse’ false fixes. Consider the idea of digital farming where a farmer subscribes to an artificial intelligence platform such as Bayer’s ‘Climate Fieldview ‘. The farmer believes they are hiring an incredibly smart AI which, after analyzing all their farm data, is giving them helpful personalized prescriptions on how to farm smarter. It may even reward them with carbon payments if they follow the prescriptions.

In reality, what is happening is that a multinational tech company is cheaply gathering large amounts of data from them that it can combine with other data from hundreds of thousands of other farmers to derive commercially valuable insights that it can sell and leverage. . Bayer is also better able to understand and nudge the farmer towards adopting farming practices that better fit its own products - upselling them its own seeds, sprays, fertilizers and engineered microbes. Thirdly Bayer establishes itself as an intermediary between desperate carbon markets looking for sequestration schemes and farmers, accruing carbon credits and taking a rent along the way. The farmer thinks they are using the tech company’s AI, but the tech company is really using the farmer (and their data and their soils) many different ways to realise extra profits and new markets.

Even more cynically a ‘solution’ may be cobbled together or promoted to push up a company’s ESG (Environmental and Social Governance) ratings for investors or to bring in environmental subsidies, tax credits and grants into a company. The Tesla car company aggressively claims carbon credits on research and production then sells them for billions of dollars. In a similar way meat companies who can show they are developing Alt Protein get a smoother ride from FAIRR’s ESG ratings and hope one day to get carbon credits too. It doesn’t matter whether electric engines or alt proteins actually help the planet - they are demonstrably already helping companies with their bottom line.

Fights against this sort of false solutionism often involve investigations and revelations to expose and take apart myths.

5. FALSE NATURE - This is false as in ” fake” or inauthentic . This reflects a value that many ordinary folks feel that better, safer, more ecologically just food systems are more likely to be rooted in intact natural ecosystems and traditional and indigenous relationships with the natural world. Genetic engineering, synthetic biology, alt-proteins , synthetic agrochemicals and geoengineering schemes are examples of ‘false nature’.

The problem is not simply that technologies like these alter nature – after all many technologies alter nature. Rather it is the depth of intervention, the level of fakery, and the fake confidence and hubris about the resilience of natural systems to survive being meddled in. Concerns also attend enclosure attempts by corporate entities to gain mastery and legal ownership over natural systems for their own private ends.

In fights over ‘false nature’, movements often point to novel risks, hubris, uncertainties and the need for precaution.

If I had a hammer…

In a way there is a sixth sort of false fakery - reflecting the maxim that “when all you have is a hammer, all problems begin to look like nails”. Too often technologists, financiers and PR folks go looking for a good news story to justify ongoing industrial investment in a particular technology and so dream up speculative “solution” stories.

Nanotechnologists looking for ways to use of nanoparticles in the food industry developed nano-thin coatings for fruits that would prevent them ripening during long distance transport. Realizing this work could get ‘development dollars’ , they subsequently argued this was a technology to help small farmers sell more into global food markets. Rather than start with a root analysis of small farmer’s problems, this solution story starts with the technology itself and is then backcast towards an ad hoc justification - a solutionist hammer looking for a problem nail to justify it.

A Food Sovereignty Talisman

To focus on root causes and discern solutionist fantasies, I am reminded of Mahatma Gandhi’s famous talisman - a heuristic he offered to help judge whether a proposed solution is the right one:

“Recall the face of the poorest and the weakest man [person] whom you may have seen,” he exhorted “and ask yourself, if the step you contemplate is going to be of any use to him [or them]. Will he [they] gain anything by it?

Will it restore him [them] to a control over his [their] own life and destiny?

In other words, will it lead to swaraj [freedom] for the hungry and spiritually starving millions?”

That question over restoring control to the poorest and weakest and hungriest is especially crucial. I suggest we could develop an additional ‘food sovereignty talisman’ to complement Gandhi’s talisman. To my mind it would go something like this:

“Who is ultimately going to benefit from this supposed “solution”?

Will it strengthen and restore Food Sovereignty to small farmers, growers, gatherers, herders, fisherfolk, indigenous people and their traditional ways?

Which food system does it best fit with?: The diverse peasant food web that feeds two thirds of humanity or the corporate Industrial food chain that feeds only a third?

Go on Try it. It helps. Some solutions sound benign enough until you try to imagine them in the context of rural peasant economies in the global South at which point they just sound ludicrous or irrelevant since they are built for the wrong food system. Will blockchain carbon credit cypto-dollars or Burger King’s bioengineered Impossible whopper burger strengthen the food sovereignty of indigenous peasant communities? it’s a pretty far stretch to make that case.

Ultimately the folks who are best placed to answer the Food Sovereignty talisman are not technologists or policymakers (or even well-meaning campaigners) but the communities themselves. That is why the best way to identify and fightback against false solutions in the food system is to support participatory processes that let those most affected assess the false fixes themselves - based on their own knowledge, experience, wisdom and practice.

The “Food System Transformation” Agenda

One good question is “Who is coming up with all these false solutions anyway?” We are now definitely seeing an uptick in false solution promotion, and I see it linked to rising rhetoric about something called the “food systems transformation” agenda.

On the surface ‘food system transformation’ sounds like a good thing that we all might want to get behind. After all most everyone wants to get away from climate-harming, biodiversity-trashing industrial food systems. Yet this specific language, while also used in a muddled way by some food movements, is not actually coming from them.

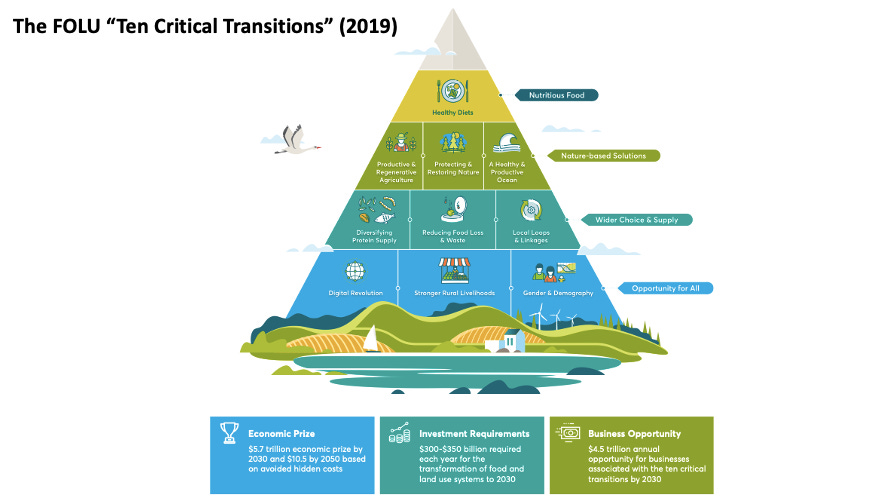

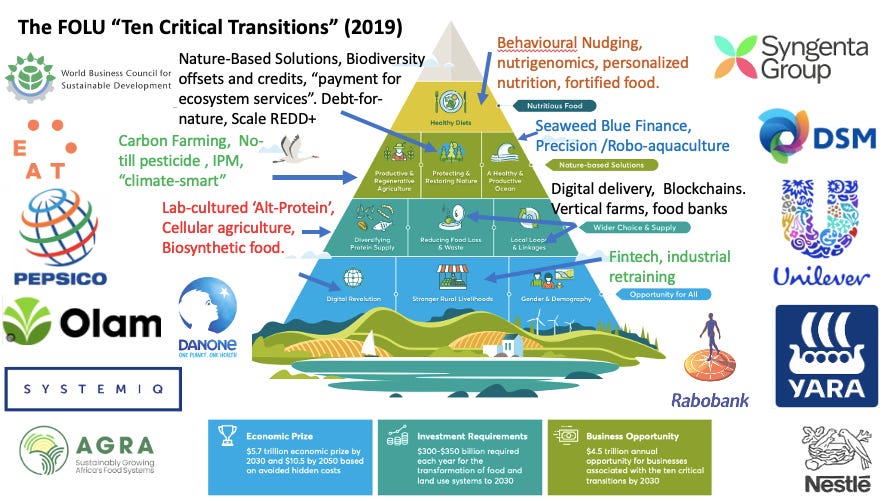

There is in fact a fairly consistent narrative now about what “food systems transformation’ means that is most comprehensively described, projected and costed by agribusiness-friendly trade groups such as the World Economic Forum, The FOLU (Food and Land Use ) coalition or the World Business Council on Sustainable Development. It’s a narrative loyally amplified by certain large green groups - such as WWF or WRI bankrolled by philanthrocapitalist funders such as the Gates Foundation and the Bezos Earth Fund.

Here for example is the triangle of ‘ten critical transitions’ that is promoted by The Food and Land Use Coalition (FOLU) in its 2019 ‘Growing Better” report. FOLU argues that governments and investors need to urgently channel $350 billion dollars extra per year towards these ten transitions to transform food systems towards ‘sustainability’.

Again, at a casual glance the ten transitions look benign enough: who doesn’t want Healthy diets, Stronger Rural Livelihoods and Protecting and Restoring Nature? but when one begins to look into how the $350 billion dollars should be spent it becomes apparent that this triangle is a fundraising portfolio stuffed to the brim with false solutions - from ‘Nature-Based Solutions’ such as REDD+ to genome editing and bioengineered alt proteins, not to mention a whole suite of corporate “digital solutions”.

FOLU is in fact just arguing for governments and financiers to plough money into exactly the sort of things big agribusiness corporations want to do anyway. And that’s not surprising when you realise who FOLU are. Hosted by the so-called “systems change corporation” Systemiq – itself a for-profit half-billion-dollar creature of the city of London financial elite - FOLU’s exact membership is a little hard to pin down. However, when it sends letters to governments they are co-signed by the CEO’s of Unilever, Nestle, Syngenta, PepsiCo, Yara, DSM, Olam, Rabobank and more. These guys don’t have the Food Sovereignty Talisman at front of mind.

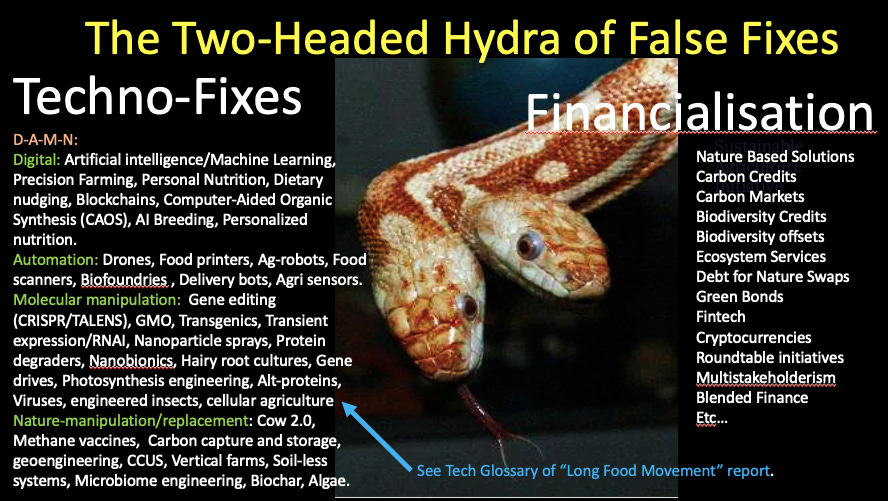

The two-headed hydra of false solutionism

Which brings me to my last slide: - What exactly are the false solutions that corporations like Yara, Unilver, Syngenta or tech billionaires like Gates and Bezos would like us to fixate on? As I mentioned before there is a wide and dizzying array of proposals out there but i think we can broadly divide them into two approaches - what I have called the “Two headed hydra of false fixes “. That is: technology fixes as the one head and financialisation of the food system as the other. It’s a hydra because ultimately these two vipers are joined on to the same body and some schemes have elements of both. In the neoliberal economy of 2023, it should be no surprise to see ‘tech;’ and ‘finance’ as the dominant solutionist themes since ‘finance’ and ‘tech’ are literally the two best capitalized, most powerful industries on the planet. Capturing the 15 trillion-dollar industrial food system is fully in their strategic plans for the coming decades.

On technofixes I’ve used a categorization scheme that we developed in the Long Food Movement report when we examined technological trends. In that scenario-building exercise about global food systems to 2045 we clustered new technological developments as being Digital, Automated, Molecular or Nature-based manipulations.

Of course many bleed across all four categories - for example InnerPlant are genetically engineering crops using synthetic biology to emit fluorescence signals to automated digital farming equipment so that farm machinery can automatically adjust their operations to better manage carbon cycles and earn carbon credits– thats D – A- M and N as well as finacialisation all in one technological ‘solution’. Several so-called ‘solutions’ bleed between tech and finance in this way- such as the use of blockchains, smart contracts and cryptomarkets to mint digital carbon credits based on use of digital farming platforms – eg See Nori’s proposed NoriToken .

On the financialisation side of the solutionist hydra we see the world of so-called ‘nature based solutions’ that is now rapidly inflating as the bubble of biodiversity finance and climate finance is being consistently applied to food systems. Luckily Kirtana Chandresekeran of Friends of the Earth international is going to talk more about nature-based solutions and financialisation

so on that note I will hand over to Kirtana. :-)

Postscript: Pathways to System Change

For those who are interested, Friends of the Earth International has recently published an excellent report on why and how to pursue a Systems Change approach (including in supporting food sovereignty). It explicitly calls out the challenge of False Solutions and calls on changemakers to be Honest, Realistic, Collective, and Inspirational. Notice they put honesty first – that may not be as reassuring as promising “solutions” but I think that’s the right way to stay with (and get through) the trouble.

That report can be found online here: Pathways to System Change: Transforming a world in crisis into a sustainable and just future

Excellent read. Up the talisman as Turing Testing for Solutionism! The systemic absence of any cultural enshrined running of corporate savior concepts through a rubric (to ferret out honest intention, to ask who benefits) is so absent as to almost be laughable if only the stakes weren't so high. Now with faux meat reconciling itself via carbon credits, the Steaks really are high, aren't they?

Really good piece. Since reading Dougald Hine's 'At Work in the Ruins' earlier this year, I've been noticing solutionism everywhere and I keep thinking about how what we have is not a problem but a predicament (I believe that is from John Michael Greer who I haven't read directly - yet). Culturally the solutionist approach is going to be a hard one to shift. I look forward to reading the documents you reference.