UN puts AI Titans on the hook for billions of dollars of biopiracy payments.

A new UN decision says AI giants should pay out billions of dollars compensation for use of AI training data . Here’s why the UN’s new “Cali Fund” sets an important precedent far beyond biodiversity.

It’s the wee hours of 2nd November 2024 in Cali, Colombia. In a large UN negotiating hall Colombian Environment Minister Susana Muhamed has slammed down the gavel on a decision that should send a jolt through the AI policy world. The decision, while seemingly about paying for genetic data, sets a significant wider precedent for how AI firms can be held accountable for stealing training data without consent or recompense.

Here is the context: After years of stand-offs and diplomatic wrangling, the United Nation’s Convention on Biological Diversity (UN CBD) this month adopted a landmark decision on something called “DSI”. DSI stands for Digital Sequence Information. It refers to digital versions of biological ‘codes’ such as DNA, RNA or the amino acids in proteins. These biological “codes” are routinely collected, stored and processed in digital form and have become the raw commodity powering the global $1.5 trillion dollar biotech industry. Originally sequenced from plants, animals, bacteria and viruses extracted from territories (plus human medical samples) the sheer volume of ‘DSI’ now stacking up in servers and databases rivals much of the text and images of the internet - and may come to surpass it.

At the recent sixteenth Conference of the Parties (COP16) of the UN CBD governments agreed to a mechanism intended to ensure that benefits arising from industrializing digital sequence information are not monopolized by private industry . The CBD’s previously agreed Nagoya Protocol requires any company using genetic resources (for example a pharmaceutical company) to pay back benefits to original ‘provider’ communities. This was to avoid ‘biopiracy’ - the colonial theft of biological material. States wrestled for fifteen years with how to also operationalize this obligation in the case of digital genetic resources. Under the new decision adopted this month corporate users of DSI are expected to pay some part of their earnings into a one-stop common fund as compensation. This fund, administered by the UN, will be known as the “Cali Fund” and It should be structured to first compensate the indigenous peoples, local communities, peasants and others whose DNA, seeds and genetic heritage was originally taken. Specifically the DSI agreement, made between 196 governments, specifies that if a company is big enough (above certain size thresholds) and uses DSI in its business then it “should” contribute either 0.1% of its overall annual sales or 1% of its corporate profits into the Cali Fund.

In the biodiversity world this agreement is a big deal. International press hailed the Cali Fund as a breakthrough move that in effect ‘taxes’ big pharmaceutical, agbiotech, cosmetics and other firms for their previously unaccountable use of DSI. While the decision isn’t as strong as South countries had hoped (companies ‘should’ pay into the fund rather than ‘shall’ pay) hope is running high that this mechanism may somehow bring in billions of much needed dollars for impoverished indigenous communities, conservation and biodiversity. In the run-up to COP16 major pharma companies such as AstraZeneca were so alarmed by this proposal that they threatened they would close down manufacturing locations or cut jobs if such a measure was passed - but pass it did. Yet all the analysis and news reports celebrating this milestone decision, missed an important reality: While big pharma players like AstraZeneca are indeed highly exposed to the Cali Fund, over time it will likely be Big Tech (especially Artificial Intelligence - AI - giants) who may be most on the hook to pay.

This is because of a little appreciated set of AI developments referred to as “generative biology”. I’ve written about generative biology already here and here (I was also recently awarded an ‘AI and Market Power Fellowship’ from the European AI and Society Fund to dig deeper into how developments in Generative Biology shift power - see here). The term ‘generative biology’ describes the use of ‘generative’ AI platforms (similar to Open AI’s ChatGPT 4 ) trained not on digital text or pictures but on billions of pieces of digital genetic data or protein data. The core idea behind “GenBio” is for AI to ‘generate’ novel DNA, RNA or protein codes - to invent new genomes, viruses , enzymes, RNA vaccines or more. Whereas generative AI chatbots are trained on billions of text fragments in order to to create novel text so the ‘gen-bots’ of generative biology rely on hundreds of millions of digital genomes for their training sets - or in other words: DSI.

And not just a little DSI. Generative biology uses a LOT of DSI. When the tech titans advertise their new ‘Gen Bio’ tools they casually boast things like this:

“We took all the DNA data that is available - both DNA and RNA data, for viruses and bacteria that are known to us - about a hundred and ten million such genomes. We learnt a language model over that and then we can now ask it to generate new genomes”

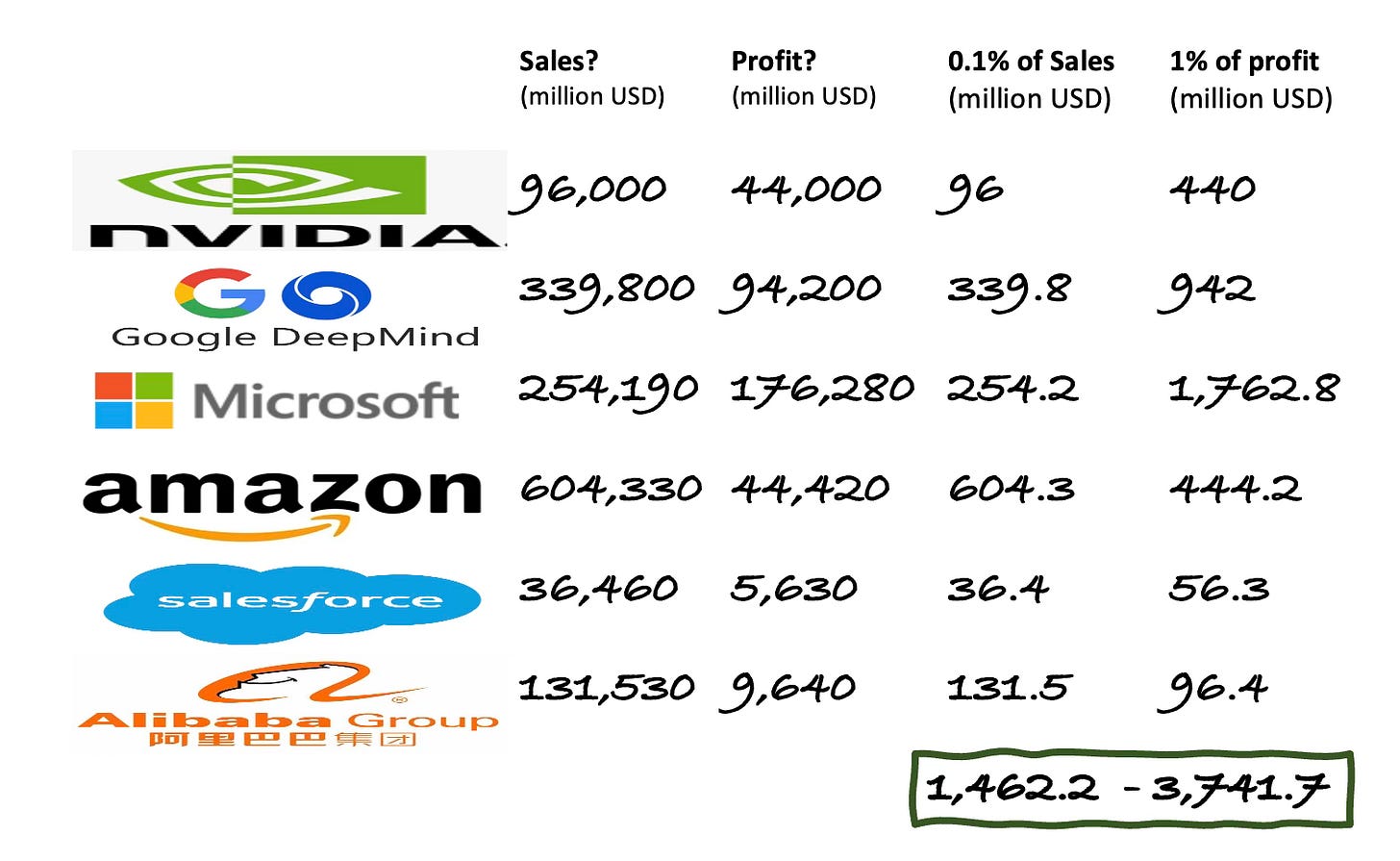

That is from Anima Anandkumar, Chief AI scientist of NVIDIA corporation. For that boast that they “took” all the DNA data read it as ‘scraped from public databases” . NVIDIA is currently the world’s third largest company by market cap. Its 12 month sales revenue to July 2024 was just over $96 billion US dollars while its 2024 gross profit was just over $44billion. So by my reckoning NVIDIA is now on the hook to pay into the new Cali Fund somewhere between $96 million US dollars (0.1 percent of sales) and $440 million US dollars (1 percent of profit). They will be expected to keep paying at this level on an annual basis.

And it is not just NVIDIA. In the report ‘Black Box Biotechnology’ I named a few more big AI giants now offering commercial generative biology tools trained on DSI. These include Alphabet (Google), Microsoft, Open AI, Alibaba, Salesforce and Amazon.

Just these ‘Big Six’’ AI giants ( NVIDIA included) should be collectively on the hook for paying between $1.5 billion US Dollars to $3.74 billion US dollars into the Cali Fund - depending whether they peg their contributions to sales or profits. (see chart below)

And to be clear there is little legal doubt that AI companies are in scope for paying into the fund. Enclosure A of the DSI agreement from COP 16 lists sectors considered to be users of DSI and therefore expected to make payments. Alongside pharma, cosmetics and the biotech sector is listed:

g. Information, scientific and technical services related to digital sequence information on genetic resources including artificial intelligence.

So there it is: On November 2nd countries came to a clear UN agreement that AI companies using DSI ‘should’ pay billions of dollars to compensate for their use of digital genetic data.

So what can we make of this?

This should impact more than genetic data - it provides a clearly agreed global precedent and framework for the principle that AI firms should pay back to providers for taking training data.

Most of the negotiators in the room were from the world of biodiversity and genetic resources policy. In this policy milieu it has long been established that a commercial player using genetic resources (seeds, genes etc) taken from elsewhere should pay back some sort of compensation to the original stewards and ‘providers’. This is what is known as the “Access and Benefit Sharing” (ABS) arrangements of the CBD. and has to be done based on Prior Informed Consent (PIC) and under Mutually Agreed Terms (MAT). The ABS approach is also reflected in the FAO Seed Treaty, the currently negotiating WHO Pandemic Treaty and the recent ‘High Seas’ agreement on Biodiversity Beyond National Jurisdiction (BBNJ). From the perspective of ABS regimes it doesn’t really matter whether you are taking a single genetic sequence from a soil sample or if you are hoovering up millions of genetic sequences to train a commercial AI model. The principle is clear. It is a simple matter of accountability and justice.

Yet in the world of Artificial Intelligence policy the question of whether an AI firm should pay society and/or individuals for the data used to train models is a raging political fight. The fact is that all of the large commercial generative AI models such as ChatGPT, Meta’s Llama or Google’s Gemini have already hoovered up petabytes of text, image, sound etc from the open internet without prior informed consent or mutually agreed terms. Ignoring copyright and other protections they have used that “taken” data to train their models. Open AI’s current $157 billion dollar valuation as a company is based entirely on brazenly stealing other people’s text, pictures, video and sound files to train models while not compensating a penny back. Indeed Sam Altman (CEO of OpenAI) has bluntly told parliaments that without being able to freely rip off copyrighted works as training data his company would not be able to make money.

Artists, authors, journalists, musicians and others have launched one after another lawsuit against AI firms for their blatant theft of other people’s materials. As the attorney for the Authors Guild , Rachel Geman, has noted, without stealing copyrighted work OpenAI "would have a vastly different commercial product.” As such, the company's "decision to copy authors' works, done without offering any choices or providing any compensation, threatens the role and livelihood of writers as a whole.” The defence by AI firms against the demand to compensate for stolen training data amounts to a weak assertion that generative AI firms, despite being the world’s richest and best capitalized companies, are acting in some sort of public interest and therefore their use of training data should be covered by ‘fair use’ doctrine. For an entirely unconvincing roundup of AI titans’ lame attempts to excuse their massive theft of training data see this roundup by the Verge.

But the DSI decision by UN CBD isn’t equivocal or even hee-hawing on this question. Instead, it starts from a clear cut and agreed assumption that theft has happened and that the use of digital sequence Information without benefits (here as training data) is wrong and “should” be compensated in line with the ABS doctrine. The decision then attempts to construct a streamlined mechanism by which firms can meet that obligation - even if the final wording doesn’t quite go the full mile in insisting. In so doing and in explicitly naming AI, the Cali Fund may be the first formal instrument anywhere to signal clearly and unequivocally that corporate use of training data (here genetic data) places an obligation to pay compensation back to original providers. For genetic data governments have settled the principle of this in line with existing ABS regimes. Now for consistency,the ABS principles of PIC and MAT should also be applied beyond digital genetic data to all data that might be causally stolen and used for training AI platforms. Those advocating for justice in thE face of AI should be holding up and waving around the COP16 DSI agreement for everyone to see. It’s a clear policy precedent for how all training data might be handled and it’s signed and agreed by almost every government on earth.

A global mandate- well sort of. Dealing with USA.

Almost every government. As noted above the CBD (and therefore the Cali Fund) was established with almost universal agreement and membership. But the ‘almost’ is not insignificant. The only 2 countries who are not party to the CBD are the Vatican and the USA., Honestly, nobody expects the Vatican to become a tax haven for AI corporations sheltering from their obligations to the Cali Fund but of course the USA - especially post-election - is another story. Generative biology leaders NVIDIA, Alphabet, Microsoft, Salesforce and Amazon are all headquartered in the US and even the Biden administration had signalled they weren’t going to request payment into the Cali fund from their domestic companies. For the Musk (sorry.. Trump) administration that attitude is likely a ‘hell no’ - unless Elon wants to exact a certain kind of twisted revenge on his AI competitors (note: X’s Grok AI doesn’t appear to have DSI/Generative Biology interests - yet).

However the fact that major AI firms are headquartered in USA shouldn’t prevent other national and regional governments from going the extra mile and requiring them to pay into the Cali fund for DSI use. NVIDIA after all sells its services worldwide as does Microsoft, Amazon, Salesforce etc. Google/Alphabet’s generative biology division (called Isomorphic Labs) is actually based in London UK (and the UK chaired the DSI negotiations and drafted the final text). Alibaba of course is firmly Chinese and China are the most recent presidency of the CBD itself. Nor should governments’ be shy to attempt to tax American AI firms when they have a UN agreement to back them up. Much of the underlying genetic data is taken from outside the USA from countries of the global south and that may be enough of a trigger for them to institute laws compelling US companies to pay. The European Union’s Competition DG has come to various decisions aimed at fining Microsoft, Google and other big tech monopolists and so could also insist that such firms pay into a DSI fund. Indeed the EU’s Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive (“CS3D”) already expressly refers to the Convention on Biological Diversity as one of the instruments companies should demonstrate compliance with and the EU has already issued a press release on the 5th November stating that “large technology companies that benefit from genetic data are encouraged to contribute to the Cali Fund.”. It’s a start. In a very parallel example Canada has struck an agreement with Google to pay an annual $100 million dollars into a fund for compensating Canadian journalists and news outlets for the way that Google (including its Gemini AI) draws on Canadian news content in its services.

Public vs private data.

There is one odd wrinkle in the Cali DSI agreement - firms are effectively being taxed for utilizing genetic data that is “in the public domain” (such as published on large genomic databases such as GenBank). AI companies who instead draw on or build private DSI databases might be presumed to have established their own DSI arrangements under ABS rules and so it is not clear if they too need to pay into the Cali fund. Presumably they have to now show they are establishing PIC and MAT for taking genetic data privately. Basecamp Research, a UK based generative biology company, claims that its AI models are trained on ten times as much digital sequence information as is held in all the public DSI databases. Instead of scraping public databases (or as well as??) Basecamp strikes private deals with communities to sample and sequence environments on their behalf, including some sort of repayment of benefits under ABS agreements. Indeed, as generative biology leaders claim that ever bigger datasets are needed to be more accurate in genomic design the need for training datasets is driving a new private bioprospecting boom - which Basecamp are at the forefront of. In Cali I was surprised to meet local community organizations already subcontracting their services to Basecamp Research under private compensation agreements. This is part of a much bigger trend underway in which digital firms are trying to gain rights to all sorts of data generated from datafying indigenous and local territories - whether to be used for genetic engineering or for generating biodiversity credits (that can be sold to ecologically damaging enterprises to ‘offset’ their impact). The power balance here feels very asymmetrical. The terms under which communities are now signing away social and ecological data to private AI firms needs to be urgently investigated.

What is and isn’t DSI - a widening scope.

Sitting through days and days of detailed negotiations in Cali one notable aspect is that the UN CBD had not authoratively placed a definition on what does and doesn’t count as DSI. Everyone agrees that DNA codes and RNA codes count as DSI while others firmly include the use of digital protein codes (eg. to generate novel proteins) . But in the side events, booths and talks beyond the DSI negotiating rooms it was very clear that tech companies are now extracting all kinds of other relevant biological information from biodiversity in digital form. Soil data, species diversity data, moisture data and even continuous recording of wildlife sounds and video might all be considered forms of ‘digital sequence information’ associated with genetic resources and of high interest as training data for AI systems. Large language AI models are already being trained to try to decode and maybe speak animal language, to monitor and maybe alter soils or to model and meddle in population structures. The principles of who is compensated when biologically derived data develops an economic value should be extended beyond simply digital DNA codes to also whatever future commercial uses of AI for environmental, ecological and biological intervention are coming down the pike.

Getting back to traceability and accountability.

If there is one big downside with the Cali DSI decision it’s that it risks breaking the original ABS obligation to pay benefits back to specific communities from whom genetic resources were originally taken. By paying into a general fund DSI users (including AI firms) might feel excused from the obligation to identify and compensate exactly those they wronged in the first place. There is also concern that monies will instead be channelled to broad unconnected beneficiaries like big green conservation NGO’s or even to support genetic engineering and sequencing projects.

What is needed therefore are initiatives and obligations to ensure that funds are channeled accountably and correctly back to the actual DSI “provider” communities. Interestingly, big data analysis and AI tools may have some role in helping identify where specific DSI came from. AI firms could be required to establish technical traceability of the DSI they use and the fund could also be empowered to support developing and implementing technologies and approaches that analyze DSI and achieve traceability back to “providers” - to ensure actual communities are accountably compensated.

What next?

Although its been 15 years in coming, the decision to establish the Cali Fund is really only the starting gun on the establishment of a much larger infrastructure and politics around DSI including how it will be integrated and used by Artificial Intelligence giants. Just as decisions on carbon accounting in the climate convention created a thicket of carbon credit and carbon offsetting markets and players, we can expect this new DSI decision will give rise to an entire universe of DSI associated counters, assessors, analysts, services, consultants, lawyers and policy pontificators. Already legal and lobbying firms are offering their services to corporate players to see if they can shield them or mitigate for the new obligations. In cash-rich AI firms such legal and lobbying firms see rich clients to service.

Early in 2025 ‘relevant organizations’ will be invited to “submit views” on the operationalizing of the COP16 decision - that will be an important moment for public interest AI policy groups, civil society and South governments to insist that AI titans be firmly kept ‘in scope; for their massive use of DSI as training data . Following this, studies will be commissioned and then in late 2025 or early 2026 there will a meeting of the CBD’s “Subsidiary Body on Implementation” to formulate recommendations to further tease out the modalities of the Cali Fund. Such detailed modalities should be adopted at COP17 in Armenia in late 2026. How the CBD finally rolls out payments to the Cali fund relevant to AI genetic training data could help set a larger direction on how AI Titans are treated for all of their appropriation and theft of other people’s data - not just their genes.